Rude word, next question

It’s not that kind of book. I’m just dropping the C-bomb there to demonstrate how effective it is as a weapon of surprise. And surprise often brings laughter with it, or at least nervous excitement.

When I’m about eight or nine I’m playing round at a friend’s flat, in Bahrain, and we begin to discuss a new word we’ve learned in the school playground – booby. It’s such a funny word. And breasts are such a mystery to us.

There are other boobies, of course: there’s the Booby bird, famous for its inability to land without crashing, like a Second World War bomber with its undercarriage shot away; the booby prize, given to someone who comes last by an embarrassing distance; and the booby trap, an unpleasant and possibly lethal surprise. But obviously the thrill of the word to us is that it pertains to a part of the female anatomy that is, in the mid-sixties, strictly off-limits.

And it’s such a funny sound. Especially when it’s repeated: booby, booby, booby, booby! The more we say it, the funnier it becomes, until we get frankly hysterical, shouting it out at the top of our voices: booby, booby, booby, booby! We laugh so hard we can’t breathe, but every time one of us gets enough breath back we shout it out again: booby, booby, booby, booby! And roll around on the floor clutching our sides.

Suddenly his mother appears at the door with a face like the wrath of God. She shouts, she hits, she slaps, and she drags us to the bathroom where she washes our mouths out with soap. Actual soap. I can still taste it as I recall the memory. And I am sent home, never to darken her door again.

Ruddy Nora – this naughty word malarkey can be quite provoking, can’t it?

I don’t hear any conventional swear words at home as a young boy. My parents do not use ‘foul language’. Throughout my childhood Dad’s three favourite phrases in times of extreme provocation are: ‘Hell’s bells’, ‘Blood and sand’, and ‘My conscience’. Though ‘Blood and stomach pills’ often creeps into the charts. I hear these frequently – always delivered in extreme anguish – railing at a world that has forsaken him. The things that occasion these outbursts are generally avoidable, which makes them all the funnier to me and my sister.

For instance, he repeatedly knocks his head on the boot catch of our Citroën ID 19.

I was about to say that he does it every time he loads something into the boot, which sounds implausible, but it’s not far from the truth: it genuinely happens more than 50 per cent of the time, which by the law of comedic repetition makes it hilarious. He does it so regularly that the skin on the top of his bald head has become paper thin, like some ancient fragment of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The slightest brush against the protruding catch brings fresh blood and misery. ‘Hell’s bells!’ he shouts, long before AC/DC use it as the title of the first track on Back in Black, and though Dad’s vocal range is an octave below Brian Johnson’s, it has almost the same intensity.

Dad never invests in a conventional tool kit. In 1975 when he decides to install central heating into our three-bed semi in Bradford he cuts the copper pipes with a serrated bread knife. It’s barely good enough to cut three-day-old bread, so hacking away at the metal tubes unleashes the beast within him. ‘Blood and sand!’ he rages, as the bread knife slips and scrapes across his knuckles.

The same year he builds a garage from a kit and uses me as his labourer. We’re about halfway through when I glance at the instructions and suggest he’s forgotten to install the internal bracing rods. ‘My conscience!’ he spits.

He forges ahead without the bracing but as we finish putting the roof on, the walls buckle slightly. ‘Hell’s bells and buckets of blood!’ he exclaims, allowing himself the full phrase in the face of this fresh test from the universe.

He tries to fix the bracing retrospectively but the ominous bulge is always there, the walls splaying by a few more millimetres every year. I don’t go into the garage much, and when I do I don’t stay long.

All Dad’s quasi-expletives are religious in origin. He’s picked them up at the Sunbridge Road Mission, that Bible-bashing fun palace: where Hell’s bells ring out to welcome sinners; where the blood of Jesus stains the sand on Calvary; and where ‘My conscience’ comes from Romans 9: verses 1–2, and goes on to proclaim that ‘I have great heaviness and continual sorrow in my heart.’

Those Methodists really know how to enjoy themselves.

Despite his close ties to the Mission, Dad did have a sense of humour. His favourite joke was about peeling onions. He told it every time he made stew – about once a week. And every time he made curry (stew with curry powder in it) – about once a month. His joke went like this: ‘The way to stop crying when you’re peeling onions is to peel them underwater – but I can never hold my breath long enough . . .’

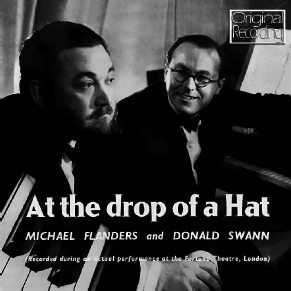

And he did have a Flanders and Swann record – At the Drop of a Hat – a live recording of their musical revue, recorded at the Fortune Theatre in London.

Michael Flanders and Donald Swann were a double act who wrote comedy songs; some about animals, some pure nonsense songs, and some satirical ones that poked fun at the social attitudes of the time. They were unashamedly upper middle class, which pleased my dad as this was something he aspired to, and presented themselves as the kind of jolly guests you’d love to have at a posh dinner party (if you had those sort of things, we didn’t). Their songs were, and still are, hilarious.

Somewhere in the liner notes, or on the back of the album cover, it was written that the show had opened at the Fortune Theatre on 24 January 1957. My birthday! This coincidence has always filled me with a sense of personal connection, possibly unwarranted, but sincerely felt nevertheless. More magical thinking.

There were songs about a gnu (and a gnother gnu); about the potential moral perils in drinking Madeira; and about redesigning the interior decor of a house to such a ridiculous extent that they actually have to sleep next door, but the most exciting track to me was ‘A Song of the Weather’.

It’s a series of twelve couplets, one for each month, describing, in a very English way, how terrible the weather is at that particular time of year. There’s ice in February, wind in March, and frost in May. The summer months are blighted with non-stop rain, and a lack of sunshine. Autumn brings mists and the occasional hail storm. And winter descends into mud, gales, fog and snow, until we get to the final, shocking line – ‘Freezing wet December, then . . . bloody January again!’

He says ‘bloody’!

The B-bomb!

Michael Flanders says the word ‘bloody’!

Well in fact they both join in for that last line. Flanders and Swann, both saying ‘bloody’. Two grown men, wearing dinner jackets and bow ties, saying, almost shouting, the word ‘bloody’, and they don’t get told off! Even my dad laughs. In fact he joins in. This in a house where swearing is most definitely not allowed. Not at all. Not a bit.

We’ve got one of those tiny mono record players that comes with us as we travel the world. It’s like a small suitcase, and the lid detaches to become the speaker. ‘Can we listen to Flanders and Swann?’ my sister and I will ask, and the record will be gently removed from its sleeve, Dad will carefully wipe it with a lint-free cloth, and reverently place it on the record-stacking spindle – his actions priest-like, as if this is some kind of sacrament. He’ll push the lever, the record will drop onto the turntable, and the tone arm will jerk across and fall onto the record with an alarming scratchy thump.

‘A Song of the Weather’ is the opening track of side two, but we can’t ask to play side two first – this would be morally reprehensible, as if we were only in it for that word. So we have to listen to side one first. We don’t mind too much, there’s the song about various forms of public transport, another about record players, the gnu song, the one about interior design, another in French which we don’t really understand but sit through patiently, and a song with a nonsense chorus (‘Weech-pop-oooh!’) which Michael Flanders encourages us to sing along to. And we do.

Side one is a little over twenty minutes long, and only serves to heighten the sense of expectation and excitement. When it comes to an end Dad removes the record from the deck. Everyone knows what’s coming but no one’s allowed to mention it. Non Mentionare. The ritual somehow purges him of any guilt. He wipes side two with the lint-free cloth and the procedure is repeated: onto the spindle, push the lever, drop, tone arm, jerk, scratch, thump – and it will start to play.

The song only lasts about a minute and a half, but as it plays my sister and I gradually lean in as we sing along. To make sure we hear it properly? To make sure, once more, that it’s true? Who knows, but here it comes . . .

‘Freezing wet December, then . . . bloody January again!’

Boom!

It’s taken almost half an hour to get here, but we’ve arrived. Mum, Dad, Hilary and me, all singing together at the tops of our voices. It’s as close as I ever get to a religious experience.

Rudeness. I think that was the start of it. Some might say the end of it, as well.

Once I get to boarding school I can indulge myself in rude language as much as I like. We’re all new to this freedom and some of us are better at it than others. One poor soul drops a catering-sized dish of baked beans onto the floor as he carries it to one of the long dining tables.

‘Bloody God!’ he exclaims, getting it fabulously wrong. Everyone laughs and the poor kid will never live it down. He is doomed to have it shouted at him for the next seven years until he leaves school. Who knows, it may have even followed him on to university or the workplace. Maybe his grandchildren still taunt him.

‘Bloody God!’ lives on with me and Rik. I tell him the story, and thereafter, whenever we want to sound amusingly uncool, we shout ‘Bloody God!’

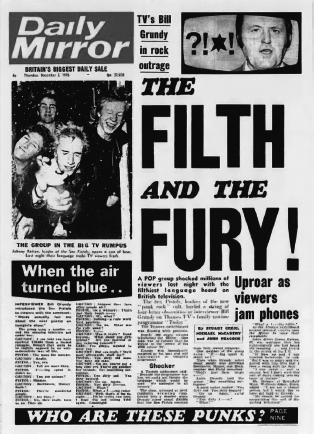

But it’s not until I get to university that the real power of swearing becomes beguilingly apparent. The Sex Pistols’ appearance on the Bill Grundy Today show is probably only watched by a handful of people – the Grundy show is a fairly tedious programme, and Bill Grundy must have been one of the main references for Alan Partridge, and perhaps Viz’s Roger Mellie ‘The Man on the Telly’. It plays in the London region to a teatime audience. On 1 December 1976 it goes out live, as usual, but the number of people who claim to have seen it rivals the trillion people who claim to have been at Woodstock.

I don’t see it live. But it’s a seminal TV moment for me.

What’s that? A seminal moment of TV that you don’t even see?

Keep reading, don’t be so impatient.

There’s no social media, no Facebook, no Instagram, no Twitter, no TikTok, the ‘internet’ is a thing no one much outside NASA and the US military has heard about. These are the days before home video recording. Days when we watch everything live and the only ‘recording’ is made in our minds. The biggest computer any of us has is a Casio calculator. Or maybe a digital watch.

We have to rely on the actual media. In this case the Daily Mirror. And I have to say they do us proud: under the banner headline ‘THE FILTH AND THE FURY’ they repeat the entire interview verbatim. It’s printed out like dialogue from a script except that none of the Pistols are referred to by name, it just says ‘PISTOL:’ or ‘GRUNDY:’ The swear words are all redacted but they helpfully put the first and the last letters down so that we know exactly what’s been said.

These are words we use every day, but it’s thrilling a) to imagine them being said on teatime telly, and b) to see the outrage they cause. Who would have thought that saying fuck or shit could make you front page news? This is the kind of power that intoxicates Rik and me.

Looking back at the actual TV recording now, it’s surprising how tame the language is. Steve Jones is the main potty mouth, but he starts off fairly gently. Bill Grundy, who looks half-cut, letches over Siouxsie Sue, who’s standing behind the band, and Steve says: ‘You dirty sod. You dirty old man.’

He could be channelling Steptoe & Son at this point – Harold’s constant rejoinder to his dad Albert is ‘You dirty old man!’

‘You dirty bastard,’ Steve Jones continues.

When we record The Young Ones five years later, bastard is still a taboo word, and there is a strict limit on how often we can use it. We use purposely childish words like ‘ploppy pants’ and ‘farty breath’ instead. In fact, they work better than swear words because they’re so pathetic. It’s not until the 1990s and Bottom that we’re allowed more or less as many bastards as we like.

But no sooner has Steve Jones broken the bastard duck when he tops it:

‘You dirty fucker. What a fucking rotter.’

What? A fucking rotter? What kind of language is that? Rotter? ROTTER? He sounds like some ne’er-do-well from an episode of Dixon of Dock Green, that homely police drama that ran from 1955 to 1976, but always felt like it was set in some mythical England back in the 1940s.

The cleverest Pistol, of course, is Johnny. He’s always very eloquent, a proper wordsmith, knows the power of words and knows what he’s saying. His only expletive in the interview almost slips out under his breath. Bill Grundy is making some asinine point about some people preferring Mozart and Beethoven and Johnny says:

‘That’s just their tough shit.’

‘It’s what?’ asks Grundy.

‘Nothing, a rude word, next question.’

This is probably the rudest line in the whole show. There’s no expletive, but the underlying lack of deference, the total disdain for Grundy, the feigned politeness, the obvious awareness that he knows more about what’s going on than the seasoned host, and doesn’t particularly care – this is the real revolution. It’s so exciting.

It’s the kind of anti-authoritarian sneer that Rik’s character Rick in The Young Ones adopts, though with Rick it becomes comedic because whenever he comes up against real authority he backs down and shows his middle-class deference – he’s a wannabe anarchist, not a real one.

But the Johnny Rotten sneer becomes shorthand when Rik and I write together – for jokingly expressing that feeling that you have no respect whatsoever for what the other person has just said.

‘Well, that’s just your tough shit,’ one of us will say, doing the Johnny Rotten head wobble and eye swivel.

‘It’s what?’ the other will reply.

‘Nothing, rude word, next idea.’

On Bill Grundy’s show in 1976 there are a total of seven rude words: three fuckings, one fucker, two shits and a bastard. Admittedly that’s quite strong for teatime telly. But by the time Richard Curtis’s generally wholesome film Four Weddings and a Funeral comes round in the early nineties there are ten fucks and a fuckity in the first minute.

Seven years later, in Bottom Live 2001: An Arse Oddity, we take swearing a little bit further.

On learning that the bar has disappeared, instead of saying: ‘What the fuck happened there?’ I say: ‘What the fucking fuckity fuck fuck fucking fucking fuck . . . fuckity fucking fuck fuck . . . fucking fuck fuckity fucking fuck fuck fuckity fucking fucking fuck . . .’ and so on, and so on, for about three minutes.

Or until people stop laughing. Each false end sounds like ‘. . . happened there’ is finally going to land. And therein lies the potential laugh – defying expectation. It’s also funny to say any word over and over again. Like ‘booby, booby, booby, booby’. And then it just becomes nonsense. In the end it’s just a noise.

When my kids are small I make a conscious effort not to swear in front of them. It’s perhaps one of the few things I inherit from my father that I like. Though I do it for a completely different reason – I want them to enjoy their swearing when they get older. Swearing is no fun unless it’s naughty. And now, as grown-ups, my girls really enjoy their Anglo-Saxon. And I too have Dad to thank for the thrill I get from a well-placed ‘cunt’. If he hadn’t made the rules so strict I might never have enjoyed breaking them.